Major issues: Trend toward CRS, CFS majors for student-athletes raises questions at Syracuse

A wall-length timeline detailing Syracuse’s storied lacrosse team, a shrine dedicated to the 2003 championship basketball team, aged photographs of teams past — sights of the Manley Field House lobby that snapshot SU’s storied athletic history.

Beyond the arrangement of glass-cased trophies and Syracuse lore are non-descript, blue double doors. Across the threshold and fixed to the wall of the Stevenson Education Center is a list of the Athletic Director’s Honor Roll behind framed glass. The names and photos brightly indicate the student-athletes who graced above a 3.0 GPA.

Adjacent to the computer labs are the offices of two academic coordinators for the Syracuse football team. Both have a hand in the education of every football player who crosses into their offices.

“They give you literally everything you need to succeed in whatever classes that you’re taking,” said Andrew Lewis, a defensive lineman for Syracuse from 2006-10, of academic coordinators.

Lewis graduated with a degree in child and family studies, a major he said he was assigned as a freshman. He wanted to study in the School of Information Studies, but said he got “behind the eight ball” his sophomore year and that the requirements to complete an inter-collegiate transfer were too difficult.

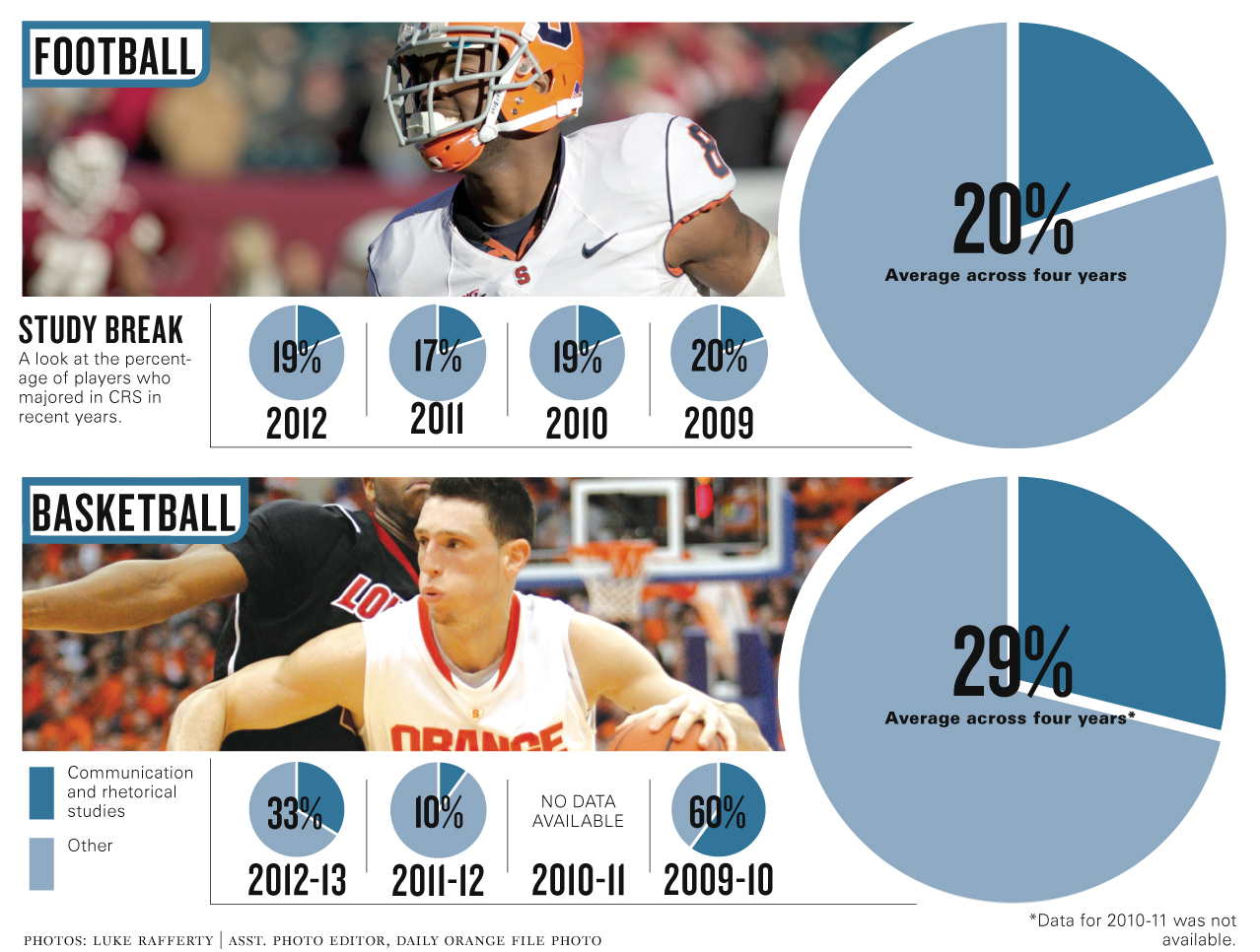

The major Lewis remained in, CFS, is one of the two most popular majors for Syracuse football players, according to data compiled by The Daily Orange using player biographies on SU Athletics’ website. The data shows that communication and rhetorical studies is the most popular major for football players for each year dating back to 2007.

From 2009-12, 20.6 percent of upperclassmen on the football team majored in communication and rhetorical studies, while 11.7 percent majored in child and family studies. On the 2012-13 men’s basketball roster, three of nine upperclassmen majored in child and family studies. The most popular majors in the university as a whole are psychology, information management and technology and architecture, according to Maurice Harris, dean of undergraduate admissions.

Finding a fit

In some instances, CRS acts as an alternate area of study for someone who was unable to get into the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications. CFS aligns well with the coaching minor offered at SU, and many student-athletes want to help people after college, officials have said. Sociology, another popular major among student-athletes, is the closest thing SU has to criminal justice.

Student-athletes interested in enrolling in more competitive colleges and programs, such as the Newhouse or the sport management major in the David B. Falk College of Sport and Human Dynamics, might not have the GPA required to enroll in the school, and instead enroll in their second-choice option, said Kevin Wall, director of student-athlete support services.

Wall said department officials would never tell a student-athlete what to major in. They merely guide them toward something of interest to that particular person.

Athletes placed into CRS or CFS out of high school sometimes have trouble meeting the requirements to transfer into an area of study more applicable to their interests, placing them, as Lewis said, “behind the eight ball.”

“Some of what students are able to do are limited based on how well they start off here at Syracuse,” Wall said, “which is why we really try to stress that first-year experience.”

Members of the University Senate Committee on Athletic Policy have a noticed a high enrollment of student-athletes in CRS and CFS, though the committee is unsure of what that means, said temporary committee co-chair Martha Hanson.

“We were starting to wonder, are athletes being guided into these in order for them to succeed,” Hanson said, adding that tight travel and practice schedules, coupled with the pressure to perform well academically can weigh on student-athletes.

Hanson said the committee is waiting on a list naming the majors of student-athletes from Jamie Mullin, the associate director of athletics for administration who serves as a liaison to the committee. Syracuse spokeswoman Sue Edson, who spoke on behalf of Mullin, said she is unsure of what list to which Hanson referred.

The faculty oversight committee on athletics conducts independent studies to gauge things like major clustering and whether student-athletes receive favorable grades in classes compared to other students, said Michael Wasylenko, a professor of economics and chair of the faculty oversight committee. The committee reports directly to Chancellor Nancy Cantor.

Wasylenko, who is also SU’s faculty adviser to the NCAA, said six or seven others help him on the committee, which conducts reviews of football and basketball student-athletes once a semester. The other sports are reviewed on a rotational basis, he said.

While the data trends toward CRS and CFS as the most popular majors for student-athletes, Wasylenko contends it is not clustering because there is no “steering” involved.

“I don’t think of this as particularly problematic,” he said. “Where it would be problematic — and it isn’t — and this has happened at other places, is the athletics department is saying, ‘You’re a student-athlete. For the convenience of the program, you should major in tiddlywinks.’

“That’s a problem. That’s steering. What we have — we don’t think — is steering these kids.”

In conjunction with academic advisers in the student-athletes’ home colleges, coordinators in the athletic program provide guidance and offer realistic thoughts on whether a student will fare successfully in a major, said Joe Fields, the men’s basketball academic coordinator.

Fields said he tries to instill the importance of education in the athletes he works with. Part of this involves the realization that a successful athletic career might only last a decade.

But some student-athletes do lose sight of that.

“Working at a university like Syracuse, there’s definitely an expectation on winning championships, winning games, competing at a high level,” he said. “Sometimes, the student-athlete you identify to come help you do so isn’t always the student-athlete that education is most important.”

Athletes that aren’t purely driven by academics, however, are often motivated to stay academically eligible to compete under NCAA guidelines, said Fields, who played four seasons as a Syracuse quarterback and had a stint with the Carolina Panthers before returning to the university as a graduate student.

The CRS major likely appeals to student-athletes — as it is to non-athletes — for its flexibility in career paths, said Kendall Phillips, an associate dean in the department. In total, about 500 students are enrolled in the CRS major, Phillips said.

Save for student-athletes’ differences in height, Phillips said they are not unlike other students. Just as some students might have time constraints with internships or part-time jobs, student-athletes commit their time to sports.

“My experience is that student-athletes are very much like every other group of students,” he said. “There are really strong students, there are those who struggle.”

Through their eyes

For student-athletes, the direction of their educations at SU depends on what they put into it.

Lewis, the former defensive lineman, said it took him too long to realize all of the resources at his disposal. If he could do it over, he would have studied something related to computers.

Lewis bought his first computer when he was 10 years old and always had that interest. He never really cared for child and family studies.

“It honestly wasn’t anything I wanted to do at the time, but I really wasn’t focused on my education and I kind of fell behind,” Lewis said.

Lewis does not know how he initially started as a CFS major. He said he believes it was based on GPA and that he was given a major he could thrive in. He did not raise his GPA high enough to transfer out of his major and into something that interested him more, though.

Across the university, inter-collegiate transfer requirements have been rising. Every school except Falk requires at least a 3.0 GPA to transfer from another college, said Renie Kehres, the assistant dean of student services in Falk and academic adviser to many athletes, including Trevor Cooney and Prince-Tyson Gulley. Kehres said Falk requires a 2.5 GPA to transfer in, though the requirements for specific majors are higher.

The NCAA’s 40-60-80 rule requires that student-athletes complete 40 percent of their degree in four semesters, 60 percent in six and 80 percent in eight. Lewis said the benchmarks for completing a major make it more difficult for student-athletes to change majors beyond the early part of college.

Kevyn Scott, a cornerback for Syracuse from 2007-11, was also a CFS major in his first semester of college, though he does not remember how he became a CFS major and said it happened by default. Scott wanted to study information management and technology, though, discovering his passion by researching majors his first semester.

“You’re, by default, placed in certain majors, and if you want to switch out, you can,” he said. “But I found that information out on my own.”

Scott said the academic support services within the athletic department were extremely helpful when he told them he wanted to move from CFS to the iSchool.

“The academic support side of things is superb,” he said.

Academic coordinators let Derrell Smith pursue his first interest: engineering.

Smith, a linebacker for Syracuse from 2006-09, graduated from a vocational technical high school in Delaware, where his concentration was engineering. While he was warned before coming to Syracuse about how hard it would be to balance football and such a difficult area of study, he was put in touch with a couple of members of the football team who were majoring in engineering.

Even so, he learned the hard way and struggled his first semester. After one semester, he transferred and became a dual major in information technology and marketing.

Smith said he was never told not to pursue engineering.

“I think it’s kind of like — imagine you being a child and you touch a stove,” Smith said. “Your parents tell you it’s hot but you’ve just got to see for yourself.”

Fields, the academic coordinator, said student-athletes are never steered toward or away from a major.

“We would never discourage them, but you probably know it’s not going to happen,” Fields said. “But you give them every avenue, every resource to explore those opportunities.”

A growing trend

Major clustering has led to a number of issues and large stories across the nation recently.

At North Carolina, an investigation showed that student-athletes were given academic benefits in the school’s African and Afro-American Studies Department.

At Georgia Tech, 82 percent of the juniors and seniors on the football team, 83 percent on the baseball team and 63 percent on the men’s basketball team majored in management in 2007-08, USA Today reported in 2008.

Those are just the headline-catchers. But B. David Ridpath, president-elect of The Drake Group, a group of college faculty, authors and activists whose mission is to protect and monitor academic integrity in college sports, said major clustering likely extends further.

“A lot of it, some of the data is unclear, but I think certainly the data that exists on this out there shows that there is a prevalence in major clustering in athletics,” said Ridpath, who is also a professor of sports administration at Ohio University.

One of the main reasons major clustering is prevalent is the battle for student-athletes to remain academically eligible and on course to graduate.

Since graduating, Lewis has started his own business with former SU football player Averin Collier. He said he has not really put his CFS degree to use specifically.

Lewis said he understands how it looks — “it looks terrible” — to have so many football players majoring in CRS and CFS. But the alternative could be more issues with academic eligibility.

“What would their GPA be in those schools, those classes?” Lewis said. “If some of these kids are barely surviving CRS and CFS classes, then we’re really going to be academically ineligible with the harder schools and the harder majors.”

But Fields, the academic coordinator for men’s basketball, said he tries to instill something far more meaningful than eligibility in the players he mentors.

“There’s still a lot of life to live. There’s still a lot of things to be accomplish. You don’t want to be judged and your character determined by what type of athlete you are,” he said. “You want it to be determined by the things you do outside the field. You have more value other than your athletic prowess.”

Published on April 29, 2013 at 3:47 am

Contact Mark: mcooperj@syr.edu | @mark_cooperjr